|

Do widzenia, Kraków; I enjoyed you.

|

Kraków, Poland – Steel shutters suddenly fall from the ceiling, causing travellers to scatter like ants in the rain.

They slide under the gates as police officers wave them along.

Confused, I stand watching the departures board at Kraków Główny, the city's main rail station. The screen only holds slots for a dozen trains, so it'll be a while before the EuroNight Chopin to Prague appears.

I lunge for an elevator to platform three, where I've been told my train will be. There are 10 tracks per platform and I still don't know which will be mine.

As I reach the top, the glass elevator doors don't open, even as a woman tries frantically to get in from the other side. We're locked down.

I'm 20 minutes to departure.

|

| Well-trained. |

Heading back downstairs, I ask a police officer if he speaks English and tell him I'm trying to get to platform three. "Then go," he says with a dismissive wave in the direction of the ticket desk.

It finally occurs to me we're not under attack, and that the station closes unneeded areas at night. I make it to platform three, but can only access the first two tracks. Both are full.

But not with my train.

The display blinks and Chopin finally shows platform three, track one; but the trains aren't moving. It updates again to two. The track is still full.

I suddenly remember reading that Polish train stations sometimes use the words for track ("tor") and platform ("peron") interchangeably. It must now be platform two, not track. Or is it?

Down to four minutes.

Again, I run at full sprint through crowds equally panicked about their trains. Someone tells me the train to Prague doesn't leave from platform two, as they hurry to Budapest. But I have to try.

Sure enough, on platform two: Chopin, idling lazily.

Having done my research, I know I'm in the second car and make the last dash.

Naturally, I'm at the wrong end of the train.

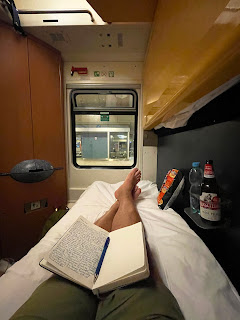

Settling into my sleeper cabin, I exhale. We begin rolling through the night and an illuminated Basilica of St. Anthony in Rybnik makes a punctuation mark on the day.

I'm loving this.